- Home

-

Overview

- Study Guide

- The Single Most Important Idea

- Mission Statement

- War Is Not Inevitable keynote speech

- Capstone Essay: "To Abolish War"

- An Action Plan

- The Nine Cornerstones

- How Far We Have Already Come

- The Secret Ingredient

- The Vision Thing

- How Long It Will Take

- What You Can Do

- The AFWW Logo Explained

- Examples of War Expenses

- Biological Differences

- What Makes People Happy

- Map of Non-warring Cultures

- Cornerstones

- Videos

- Books

- Blog

- Project Enduring Peace

- About

- Related Projects

- Contact

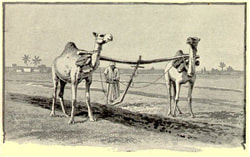

To Date, Nonviolence Movements Were"Before Their Time." Now They Are Poised to Change History9/16/2019  THE TIMES, THEY ARE A CHANGING Agricultural Revolution. Industrial Revolution. Digital Revolution/ Information Age. Massive alterations in outlook and behavior have accompanied each of these profound shifts in human culture. No writer has come close to the masterful chronicling of the pell-mell morphing of our time to be found in two classic works written in the late 1900s by Alvin and Heidi Toffler: Future Shock and The Third Wave. Both books still make fascinating and highly instructive reading. It's likely in moments of reflection you feel an uncomfortable stirring, a tightening sense of unease and uncertainty in your chest. Change tends to disturb us. And if anything, the speed of change so brilliantly limned by the Toffler's seems to continue its breathtaking acceleration. We are creating, with every day that passes, the very different future in which we and our children will live. These astonishing changes are propelled by myriad social pressures and technological inventions. It's not a question of whether we'll experience a massive cultural upheaval—a "great turning," a "paradigm shift," a cultural transformation. Right now we are, in fact, experiencing a huge one. The question is whether the change will be mostly violent or mostly peaceful and where will we end up. Skeptics and "hard core realists" can quite legitimately question the notion that as a key tool to affect this transformation, we might purposefully embrace a profoundly less violent world view. With a critically cocked eyebrow or perhaps a slightly patronizing smile they can ask, "If nonviolence movements have the power to transform our societies—create a great paradigm shift from cultures steeped in violence at every level to ones that embrace nonviolence—why haven't they already achieved this transformation? Furthermore, what makes you think these methods are poised to succeed now?" I'll share my opinion about these two questions shortly. First, however, we need to establish some perspective on nonviolence movements, in the present and the recent past.  Alice Paul (1885-1977) Alice Paul (1885-1977) NONVIOLENCE WORKS Alice Paul is one of my heroes. She was pivotal in the U.S. suffragist's "civil disobedience" movement to give women, including me, the right to vote. She was courageous, willing to endure arrest, imprisonment, and force-feeding for her cause. And she exemplifies masterful use of the "media," organizing parades, marches, and the first picket line in front of the White House. But most especially, she's my hero because she was a woman who knew when not to compromise. Willingness to compromise is critical to making and keeping peace—and it is, by the way, a trait much more characteristic of women than men—but sometimes there are issues about which compromise is unacceptable. In order to avoid creating excessive ill will from the public and a wide variety of authorities, women in other suffragist groups of her day were willing to secure women's right to vote on a piecemeal, state-by-state basis. Paul saw clearly that this would only create laws relatively easily repealed at some future whim of each state's electorate. She fought without compromise for a constitutional right that had been exercised from the country's beginning by white men, and later extended with the 15th Amendment to black men. Paul's inner vision said that this "right" for women had to be in the Constitution. She refused to settle for less. An engaging way to learn about Alice Paul and her movement is the movie "Iron Jawed Angels." The actress Hillary Swank does a masterful job of depicting Paul's ten year struggle not only with other women's groups, but also her joy in 1920 on the day the 19th amendment to the constitution was ratified. (Sheri Browne offers an interesting article on Paul). Alice Paul, the daughter of Quakers, is especially dear to me because her brilliantly led campaign to do this extraordinary thing was nonviolent. At roughly the same time, the modern age's indisputably most famous and most systematic theorist and practitioner of nonviolence, Mohandas K. Gandhi, was beginning his long career. He started in South Africa (1893-1915), but before going there, Gandhi had observed first hand in Britain the successes being made by British suffragists. He admired much of their efforts, although he ultimately rejected their occasional use of violence (e.g., tossing bricks through windows and setting fires). As his ideas developed, he decided that his movement was to be based entirely on "nonviolent non-cooperation with injustice." During his struggles to win civil rights for the Indian community in South Africa, he acquired further insights into the power of nonviolent noncooperation as a method for achieving social transformation. He became aware of the philosopher in the United States, Henry David Thoreau, who in 1849 had penned a remarkable treatise on nonviolent action eventually called "Civil Disobedience" which shared many of Gandhi's ideas. He may even have known about Alice Paul. After twenty years, in 1915, he returned to India, the country of his birth. India was at that time the most brilliant jewel in the crown of the British Empire, gifted with such riches as spices, gems, cotton, sugar, indigo, calico, and raw silk. The British could not remotely conceive of living without India, which was in many ways the empire's financial foundation.  Mohandas K. Gandhi Mohandas K. Gandhi Gandhi was headed into what could only be a gargantuan struggle. He wanted to end British rule in India, and his vision was to shape a future after his people had achieved the dignity of independence in which Hindus and Muslims lived together in peace, an example for the world. Due in no small part to his tireless and determined efforts over several decades—marches, writing, imprisonment—his homeland won independence in 1947. He had stated that he wanted to use India to show that nonviolence on the part of resisters can succeed in bringing about major transformation. In that, he succeeded. Sadly, Gandhi's greatest vision, of a united and peaceful India, was not to be. Separatists wanted to partition the country into Hindu and Muslim states. Their cause won, and the country was partitioned into India and Pakistan. We continue to live with that result. Fighting soon began in earnest, and on January 13, 1948, at the age of 78, Gandhi began a fast with the purpose of stopping bloody sectarian rioting by thousands. After five days, the opposing leaders pledged to stop the killing, and Gandhi broke his fast. He was still urging accommodation between Muslims and Hindus, and a Hindu radical who opposed the partition felt that Gandhi had betrayed Hindus. Twelve days after Gandhi broke the fast, the man assassinated Gandhi with three point-blank shots to the chest. We continue to live with that result as well. Who knows what "might have been," even in spite of partition, had Gandhi lived to give more nonviolent guidance to his country's leaders. His profoundly moving story is a study in the awesome power of nonviolent action to create huge and lasting social change, although not without great sacrifice. His struggle is famously portrayed by the actor Ben Kingsley in the epic film "Gandhi ." Gandhi's goal included freedom from the yoke of British rule, and freedom won by love, not by guns. Not only did the British ultimately leave India voluntarily, they left on terms friendly enough that India and Britain remain allies to this day. The nonviolent methods used by practitioners like Alice Paul and later Mohandas Gandhi have not yet transformed the world. Nonviolence as a way of life, a way of resolving conflicts, clearly has not become the world's fundamental guiding philosophy. But as remarkable—and to many people as unbelievable—as the possibility of using nonviolence to shape our future in positive ways may seem, a great many nonviolent movements are at this very moment working passionately and intelligently to do just that. And what may surprise many of the readers of this essay is that there is, for the first time in recorded history, a genuine chance that they may succeed. There's another pioneer nonviolence movement that deserves extremely high profile but remains virtually unknown by most people. It's an example of how nonviolence, correctly applied, has the astounding power to bring about positive change in the most surprising places. It teaches that there is no social, financial, or religious limit to its potential.  Abdul Ghaffar Khan and Mohandas K. Gandhi Abdul Ghaffar Khan and Mohandas K. Gandhi In the 19 October 2008 issue of the Los Angeles Times, Alan M. Jalon wrote an extensive review of a new documentary film about the long life of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, often called Badshah Khan. (i) This imposing 6'3" tall Pakistani Pashtun tribal leader was a contemporary and follower of the relatively diminutive Gandhi. Khan died in self-imposed exile in 1988 at the age of 98. He started by buildings schools throughout the region of northern India that is now Pakistan and Afghanistan, and he traveled, taught, and recruited extensively. At one point in this traditionally very aggressive region steeped in an ethos of revenge, Khan had built an army of nearly 100,000 Islamic followers sworn to the use of nonviolent methods to resist British control of their land and lives. (i ) His soldiers wore uniforms and maintained military discipline but did not carry weapons as they opposed British efforts to keep them subjugated. They stood before their opponents unarmed, suffering beatings and jail. The British were deeply afraid to lose control of the Pashtun region because this was the buffer zone needed to keep Russia out of India, the empire's most critical possession. As a result, British efforts were uncharacteristically brutal. Whole villages were destroyed. Many people were killed. Being assigned to Northern India was the toughest assignment a British soldier of the time could draw. Don't rush past this profound fact. Clearly if Khan could achieve this among notoriously warring Pashtuns, the potential for peaceful change exists even in the world's remotest and violent areas, in the most violent of hearts—indeed, Gandhi said: "There is hope for a violent man to become nonviolent, but none for a coward." Note also that religion is not the problem when it comes to divesting ourselves of violence; rather, the key is leadership that leads out of an uncompromising nonviolent vision. Gandhi eventually gave this assertive but nonviolent approach to social transformation the name satyagraha, which literally means "clinging to the truth." It is often translated as "soul force" or "truth force." There are, of course, subtle differences in meaning between these several terms (civil disobedience, nonviolent non-cooperation, satyagraha, soul force), but they refer to a process so similar that I use them interchangeably. Fundamental to satyagraha is the principle that nonviolence practitioners must seek to convert their opponents, not beat them or destroy them. The goal is to win them over without using physical force. And the nonviolent non-cooperator must be willing to suffer, if necessary, to do so. This approach must not be mistaken for "passive resistance": there was, and is, nothing passive about satyagraha and it's certainly not limited to resistance. Martin Luther King Jr. called it "love in action."  Hope or Terror by Michael Nagler Hope or Terror by Michael Nagler RECENT EXAMPLES OF THE SUCCESSES OF NONVIOLENCE One of the most succinct and clear explanations of these terms and of the general principles of satyagraha that you can treat yourself to is found in a small pamphlet, Hope or Terror, by professor Michael Nagler. (ii) Other nonviolent movements have followed those of Paul , Gandhi, and Khan and each has succeeded at some level. According to Nagler (iii), who cited figures taken from the book Peace is the Way, (iv) the number of such movements has grown since 1948 both quantitatively and qualitatively. "In one year alone, 1989-1990, there were thirteen uprisings against despotic rule," of which twelve were essentially nonviolent. "The exception, Rumania," he points out, "was by far the most violent revolution of the post-Communist transitions—and characteristically accomplished the least. All but one of the remaining twelve, the disastrous Tienanmen uprising in China—led their participants to freedom." Nagler also points out that these uprisings (in, among other places, Latvia, Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Hungary, Indonesia, and Chile) "embrace a population of 1.7 billion people, or 1/3 of the planet." He sums up: "If we step back and look at the whole past century, getting India also into the net, an astounding 3.3 billion people, or more than half the human population on the earth, now enjoys freedoms that were formerly denied to them (and in most cases could never have been secured by force) thanks to Satyagraha." THE PROBLEM OF BACKSLIDING It's clear from these many examples that nonviolent civil disobedience has the power to transform. What is also clear is that too often the progress made is eventually lost, examples being the uprisings in the Philippines, in South Africa, in Serbia and the Ukraine. (v) Certainly no one would suggest that our dominator governing systems around the globe have been transformed into egalitarian ones. Even more disappointingly, humanity's entrapment in violence in the form of domestic violence, civic violence, and war persists. Gandhi died having experienced the profound disappointment of civil war and the partition of India along religious lines. Why was that? Why did things ultimately fall apart in India? Why is Russia in 2008 slowly but inexorably loosing democracy, slipping back into authoritarianism? Why is Pakistan, after all of Badshah Khan's great success is the area where he lived, now embroiled in a brutal shooting war with India in Kashmir and infested along its border with Afghanistan with Muslim terrorists. Why despite the examples of Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela has nonviolence not yet transformed the whole world? For that matter, why did the nonviolent teachings of Jesus ultimately get twisted by all but a few small groups that appeared now and then, such as the Quakers, into "business as usual?" The reason is not because guns and bombs or even financial or political power are more powerful than satyagraha. When hundreds of thousands of men, women, children, the aged, and the weak are led by a leader who knows how to train followers in nonviolent action, nonviolence will defeat even guns, bombs, and the secret police. The numerous nonviolent revolutions cited by Nagler also make clear that even without the guidance of a charismatic figure, ordinary people acting nonviolently can produce significant shifts. Harvard professor Gene Sharp wrote extensively on the strategies and tactics of successful and enduring nonviolent movements (xv). The world is not yet convinced of this truth, however, despite the notable examples just reviewed. The vast majority of people still view these instances as rare historical flukes, exceptions and not a process we can adopt systematically. Or they are viewed as irrelevant or impossible to use in a world that has gone way too violent. This commonly shared ignorance and/or skepticism is at the moment, in my view, the single biggest barrier to the successful adoption and application of nonviolence. Using this method of transformation will not be broadly adopted until we convince a critical mass of people and leaders that it works. But the point of this essay isn't to argue that civil disobedience works—it clearly does (vi) —but to explain why the results too often do not persist and the technique itself does not spread like wildfire, transforming every culture, every society, in its path. Why hasn't the nonviolence of Jesus or Buddha or the suffragists or Gandhi not yet transformed our violent, warrior cultures into the reality of living in peace?  A SEED MUST BE PLANTED IN FERTILE GROUND There was a famous wine commercial in which the pitch man, the impressive actor and director Orson Wells, would claim that ""We will sell no wine before its time." I believe all historical peace movements with which we are familiar—from before Jesus and including Buddha and all the other wise men who preached love and compassion rather than violence—up until roughly the end of the 20th century, were "before their time." The world wasn't ready for them. Wasn't ready to listen. Wasn't ready to learn. Wasn't ready to act. From all of these nonviolence predecessors we learned much: about ourselves as humans and about our aspirations and longing for a less violent society. Each in their way laid a foundation for the practice of nonviolence. But the environment into which all earlier nonviolence movements were offered wasn't an environment within which they could persist and deliver massive social transformation of our dominator cultures for two principle reasons. First, because the global community had not yet reached the end of its rope. Each time such a nonviolent, peace-seeking movement arose, most people felt that how the world worked was still okay, or at least was still tolerable, or was simply the way things have always been and you just had to deal with it. You might have to pick up and migrate elsewhere if you were really, really unhappy, persecuted, or in dire poverty. But at least there were still elsewheres to go to. Now, for all practical purposes, the world is full. Our backs are to the wall, so to speak, when it comes to emigration to escape the worst. For example, we had not yet created inescapable environmental destruction on a scale so massive that it is life- and civilization-threatening (ozone holes, dying coral reefs, melting glaciers and ice caps, radical changes in global temperature and vegetation distribution). We still had not yet created weapons of mass destruction capable of literally obliterating whole populations or poisoning the entire global environment. In recent history, many of the world's most powerful leaders and denizens believed that democracy and capitalism would create wealth, freedom, and happiness for all. In that democratic world with its free-market capitalism the causes of violence would fade. With the recent collapse of the United State's capitalist market and the spread of financial crisis around the world, the idea that unbounded capitalism and democracy has the capacity to cure the problem of poverty, let alone violence, is pretty much dead. Pick your own favorite catastrophe in waiting. Whether we know it or not consciously, all of us have arrived at the end of the rope, and those who are paying close attention are convinced. Masses of people, at last, are ready to listen, ready to consider some other way. Our survival instinct is aroused. It tells us that we are urgently in need of a way out...in need of transformation. Second, none of these previous nonviolence movements, including the suffragists, recognized fully the critical, key role women must play to temper human male inclinations for dominance using force. (vii) The suffragist and feminist movements of the late 1800s and early 1900s had not begun to approach maturity even in the developed world; in the early 1900s, women had only barely won the right to vote. Many years of struggle lay ahead to allow women to gain the education, financial resources, and legal rights that are the backbone of empowerment. The nonviolence pioneers of the 20th century, and for that matter, all centuries preceding it, had no idea that for their movement to not only succeed but persist, a necessary requirement was that they fully deploy, in significant numbers, the natural allies of nonviolence and social stability...women. I repeat this vital point: women, in general, are the natural allies of nonviolent conflict resolution in a way that men, in general, are not. For example, studies show that in decision-making situations where two sides are in conflict, women are more inclined to use compromise and negotiation as a first choice rather than adopt a win/loose strategy, something more characteristic of men. The reasons for these gender differences when it comes to resolving conflicts are explored elsewhere. (viii) The significance of this difference, however, is that along with many other necessary changes required of us in the way we live if we are to transform our societies and abolish war, (ix) we need to empower women. Empower them not only as efficient workers in the cause, but women as leaders and governors. Women who are sharing in decision-making after the cause is won. Instead, for the past millennia of recorded history, women were kept out of such public policy making.  It was not always so for our species. The nomadic hunter-gatherers of our deep past lived in egalitarian and for the most part nonviolent social groups in which women shared equal power with men and social groups moved from place to place. The anthropologist Douglas Fry describes their lives with reference to violence and points out that something about settled living changes our ways of dealing with each other. (x)  Among these changes, three notable shifts occur when hunter-gatherers cease being nomadic. The reasons for the alterations are still being debated and requiring explanation: development of hierarchical social structure, subjugation of women, and war. Consequently, taking off in earnest at the time of the Agricultural Revolution, roughly 10,000 years ago—the time of great settling down—women's public input and power began a long, agonizing decline when it came to influencing matters of violence and war, and much else as well. (xi) Societies without meaningful feminine voices in governing have created hierarchical dominator cultures, a natural inclination of human males. In these societies status and power are enforced with violence, first in our homes, then in our communities, and by extension, between nations. (xii) History is mostly the story of how a minority of men have led society after society, culture after culture, civilization after civilization into war. So this new reempowerment of women is the second reason we are finally ready to listen. Women in substantial numbers, at least in the developed world, have begun to reclaim public power, including governing power, and their innate preference for nonviolence in the face of serious conflict is working its way into every nook and cranny of their societies. Knowledgeable observers are beginning to concede openly and document the critical importance of women's voices at all levels of governing if we are to create and sustain a less violent future. (xiii, xiv) The women, half of humanity, definitely are listening. GETTING WOMEN FULLY ENGAGED To offer one example of women stepping up to the responsibility of governing, in mid-November of 2007, over seventy five women—current and former heads of state, influential ministers, and leaders of inter-governmental and non-governmental organizations—were invited to the first International Women Leaders Global Security Summit at the Jumeirah Essex House Hotel in New York City. Note that the subject was "global security," not "national security." The co-hosts were former Irish President Mary Robinson and former Canadian Prime Minister, Kim Campbell. These women convened to discuss, evaluate, and endorse meaningful strategies for securing positive change (read about the meeting here). Similar, earlier meetings have likewise stoked the process of energizing women, one of the highpoints being the "Fourth World Conference on Women" in Beijing in 1995. It was there that the U.S. President's wife, Hillary Clinton, the woman who a short 14 years later would become the U.S. Secretary of State, forcefully addressed women's issues, telling delegates from more than 180 countries, "If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women's rights and women's rights are human rights, once and for all." Six of the seven living women Nobel Peace Laureates have organized their own response, The Nobel Women's Initiative, to changing the way we run our societies in the hopes of ending war--Jody Williams, Shirin Ebadi, Wangari Maathai, Rigoberta Menchú Tum, Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan Maguire (the seventh, Aung San Su Chi, is currently imprisoned in Myanmar). African women, suffering terribly from poverty, AIDS, and war, are getting particularly fed up. For example, in Liberia in 2003, Christian and Muslim women banded together to use nonviolent means to force their dictator president to the negotiating table and ultimately they won a peace treaty (this remarkable, modern day successful peace movement is documented in the film produced by Abigail Disney and narrated by one of the Liberian women, Leymah Gbowee: "Pray the Devil Back to Hell." This website provides a step-by-step guide that follows the action in the film, pointing out each of the things the women did that achieved success. At the each step the guide explains, as a learning tool, why and how what the women did illustrates the best practices of a successful nonviolent direct action, in this case to end a war. OUR TIME FINALLY PROVIDES THAT FERTILE GROUND Why, then, were former nonviolence efforts unable to create lasting transformation of our cultures? I suggest it's primarily because of these two barriers:

Elsewhere, in an essay entitled "How Far We Have Already Come," I describe six key changes or innovations, going back some 700 years, that were necessary predecessors of our ability now to abolish war, one of our most despicable forms of violence, if we choose. These building blocks are:

Like the two changes highlighted in this essay—recognition of the necessary role women must play and that we are finally ready to listen—these six building blocks also make our time different. But our time isn't just different. It's radically different. These eight preparatory changes have set the stage for a massive paradigm shift that favors, although it does not guarantee, a future civilization characterized by a number of wonderful things, among them an ethos of nonviolence. Fortunately, because of the labors and sacrifices of those who went before us—before sufficient numbers of us were ready to listen—we don't need to reinvent the wheel: we don't need to discover how nonviolence works or how to implement it. Their experiences, their trial and errors, their knowledge of how to make nonviolence work for us, all of these are like a fabulous wine laid aside for us to drink when the time was right. In our time, nonviolence can finally work its magic. Our challenge, our pleasure, is to uncork the many stored bottles laid down by the pioneers of satyagraha and begin to dispense the elixir liberally.  A WARNING AND ALSO HOPE I would prefer to end on this positive note. I must, instead, close with a warning. With all of this positive promise going for us, the very worst thing we can be is complacent, so buoyed by the positive that we overlook the negative, and thereby ultimately loose the struggle. Nonviolence is a powerful positive force. Equally powerful negative forces arrayed against us never sleep. They don't take time out for vacations. They certainly don't take time out to smell the roses. Principle among these I would list the spreading sickness of terrorism, the persistence of ignorance, the ease of sloth or indifference, the potential social and cultural breakdown as negative consequences of global climate change assail us, and the extraordinarily motivating force and deeply entrenched culture of violence and greed. We are in a race, a terrible race, and the stakes could not be higher. I sense in some sectors of various peace movements the idea that love is so powerful, we can simply love our way into that better future. This incorrect assumption was among the chief sources of failure of some former generations of peace activists such as the hippies of the 1960s. Jesus certainly preached such love, as have other great souls of the past, but all such movements were eventually co-opted. Satyagraha depends on love, but it also depends on willingness to learn discipline and to suffer. In some cases, I've heard well meaning proponents of a great positive shift in our time argue that such a shift is an ordained outcome of human spiritual evolution. That the triumph of love and peace is inevitable. There is danger here. If we assume that the Age of Aquarius is our destiny and assuming its inevitability undermines our determination and willingness to suffer to win this change, we very well may see this extraordinary historic window of opportunity tightly close. We need to act forcefully, quickly—and without compromise. If we fail, we may be forced to settle for something far less grand for our descendents than our vision of a peaceful future. Nonviolence is a mighty technique for social transformation; it is not a guarantee. There has, however, never been a time more favorable for men and women, as full partners in the practice of nonviolence, to do their work. Acknowledgments I wish to thank the following for their thoughtful, insightful critiques of this essay while I take full responsibility for its content: Chet Cunningham, A.B. Curtiss, David Hurwitz, Peter Johnson, Tim Kane, Al Kramer, Peggy Lang, Bev Miller, Michael M. Nagler References

i Easwaran, Eknath. 1984. Nonviolent Soldier of Islam. Badshah Khan, a Man to Match His Mountains. Tomales, CA: Nilgiri Press. ii For an excellent and succinct introduction to satyagraha, the work of Gandhi, basic principles and training in the practice of satyagraha, and contemporary examples see Hope or Terror? Gandhi and the Other 9/11 by Michael N. Nagler. Minneapolis, MN: Nonviolent Peaceforce and Tomales, CA: Metta Center. To obtain copies go to: Metta Center: Hope or Terror: Gandhi and the Other 9/11. iii ibid iv Wing, Walter with Richard Deats. 2000. Peace is the Way: Writings on Nonviolence from the Fellowship of Reconciliation. NY: Orbis Books. v Nagler, Michael N. Gandhi and the Other 9/11. Minneopois, MN: Nonviolent Peaceforce. p. 32. To obtain copies go to: Hope or Terror: Gandhi and the Other 9/11. vi Stephan, Maria J. and Erica Chenoweth. "Why civil resistance works. The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict." nonviolent-conflict.org/PDF/IS3301_pp007- 044_Stephan_Chenoweth.pdf vii Hand, J. L. 2003. Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing. Hand, J. L. "The Secret Ingredient." viii Hand, J.L. 2003. Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing. ix For discussion and examples of the numerous key challenges that must be addressed to accomplish the goal of abolishing war see the nine "cornerstones" on this website and summarized here. x Fry, Douglas. 2006. The Human Potential for Peace: an Anthropological Challenge to Assumptions about War and Violence. New York: Oxford University Press. 2009. xi Eisler, Riane. 1987. The Chalice and the Blade. NY: Harper Row. Hand, J. L. 2003. Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing McElvaine, Robert. 2002. Eve's Seed: Biology, the Sexes, and the Course of History. NY: McGraw Hill Publishers. xii Eisler, Riane. 2007. The Real Wealth of Nations. Creating a Caring Economics. San Francisco, DA: Barrett-Koehler Publishers. — Hand, J. L. 2003. Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing. — McElvaine, Robert. 2002. Eve's Seed: Biology, the Sexes, and the Course of History. NY: McGraw Hill Publishers. xiii A small sample of many works that explore the reasons why women are critical to creating a better future: — Fisher, Helen. 1999. The First Sex – the Natural Talents of Women and How They are Changing the World. NY: Random House. — Hand, J. L. 2003. Women, Power, and the Biology of Peace. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing ---Hand, J. L. 2018. War and Sex and Human Destiny. San Diego, CA: Questpath Publishing. Full text available for FREE at J. Hand personal website [follow nav bars "Publications" > "Nonfiction"] — Myers, Dee Dee. 2008. Why Women Should Rule the World. NY: Harper Collins. — Wilson, Marie. 2004. Closing the Leadership Gap: Why Women Can and Must Help Run the World. NY: Viking. xiv In 2003, Donald K Steinberg was appointed Director of the U.S. Department of State/U.S. Agency for International Development Joint Policy Council. He is a career diplomat in service to the United States for 27 years in places like Angola, South Africa, and Afghanistan. In 2004 he delivered a lecture at the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice, University of San Diego, San Diego, CA. His title was: "Conflict, Gender, and Human Rights. Lessons Learned in the Field. Equally important (to reconstruction efforts after war) is a strong emphasis on the role of women, not just as victims of conflict, but also as the key to preventing and ending conflict. This isn't just a question of fairness or equity. Bringing women to the peace table improves the quality of agreements reached, and increases the chance that these agreements will be implemented successfully, just as involving women in post-conflict governments reduced the likelihood of return to war. Reconstruction works best when it involves women as planners, implementers, and beneficiaries. The single best investment in revitalize agriculture, restoring health systems, reducing infant mortality, and improving other social indicators after conflict is girls' education. Further, insisting on full accountability for actions against women during conflict is essential to rebuild rule of law." Steinberg, Donald K. 2004. "Conflict, gender, and human rights: Lessons learned from the field." San Diego, CA: Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace and Justice. (p. 34) xv Sharp, G. 2005. Waging Nonviolent Struggle. 20th Century Practice and 21st Century Potential. Boston: Porter Sargent Publishers, Inc.

1 Comment

|

Follow Me on Facebook

If you'd like to read my take on current affairs, or get a sense of what amuses me or I find educational or beautiful, do a search and follow me, Judith Hand, on Facebook. About the AuthorDr. Judith L. Hand. Dr. Hand earned her Ph.D. in biology from UCLA. Her studies included animal behavior and primatology. After completing a Smithsonian Post-doctoral Fellowship at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., she returned to UCLA as a research associate and lecturer. Her undergraduate major was in cultural anthropology. She worked as a technician in neurophysiology laboratories at UCLA and the Max Planck Institute, in Munich, Germany. As a student of animal communication, she is the author of several books and scientific papers on the subject of social conflict resolution.

Categories

All

Archives

November 2019

|

A Future Without War

Believe in it. Envision it. Work for it.

And we will achieve it.

Believe in it. Envision it. Work for it.

And we will achieve it.

AFWW is continually developed and maintained by Writer and Evolutionary Biologist Dr. Judith Hand.

Earth image courtesy of the Image Science & Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center. Photo Number AS17-148-22727 eol.jsc.nasa.gov

©2005-2019 A Future Without War. All rights reserved. Login

Earth image courtesy of the Image Science & Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center. Photo Number AS17-148-22727 eol.jsc.nasa.gov

©2005-2019 A Future Without War. All rights reserved. Login

- Home

-

Overview

- Study Guide

- The Single Most Important Idea

- Mission Statement

- War Is Not Inevitable keynote speech

- Capstone Essay: "To Abolish War"

- An Action Plan

- The Nine Cornerstones

- How Far We Have Already Come

- The Secret Ingredient

- The Vision Thing

- How Long It Will Take

- What You Can Do

- The AFWW Logo Explained

- Examples of War Expenses

- Biological Differences

- What Makes People Happy

- Map of Non-warring Cultures

- Cornerstones

- Videos

- Books

- Blog

- Project Enduring Peace

- About

- Related Projects

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed